Популярные статьи

- Государственно-частное партнерство: теория и практика

- Международный форум по Партнерству Северного измерения в сфере культуры

- Мировой финансовый кризис и его влияние на Россию

- Совершенствование оценки эффективности инвестиций

- Качество и уровень жизни населения

- Фактор времени при оценке эффективности инвестиционных проектов

- Вопросы оценки видов социального эффекта при реализации инвестиционных проектов

- Государственная собственность в российской экономике - Масштаб и распределение по секторам

- Кластерный подход в стратегии инновационного развития зарубежных стран

- Перспективы социально-экономического развития России

- Теория экономических механизмов

- Особенности нового этапа инновационного развития России

- Экономический кризис в России: экспертный взгляд

- Налоговые риски

Популярные курсовые

- Учет нематериальных активов

- Потребительское кредитование

- Бухгалтерский учет - Курсовые работы

- Финансы, бухгалтерия, аудит - курсовые и дипломные работы

- Денежная система и денежный рынок

- Долгосрочное планирование на предприятии

- Диагностика кризисного состояния предприятия

- Интеграционные процессы в современном мире

- Доходы организации: их виды и классификация

- Кредитная система: место и роль в ней ЦБ и коммерческих банков

- Международные рынки капиталов

- Многофакторный анализ производительности труда

- Непрерывный трудовой стаж

- Виды и формы собственности и трансформация отношений собственности в России

- Анализ финансово-хозяйственной деятельности

Навигация по сайту

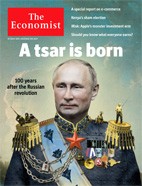

The Economist - 28 октября 2017 |

|

Год выпуска: октябрь 2017 Автор: The Economist Newspaper and The Economist Group Жанр: Экономика/Политика Издательство: «The Economist Newspaper Ltd» Формат: PDF (журнал на английском языке) Количество страниц: 100 Описание: As the world marks the centenary of the October revolution, Russia is once again under the rule of the tsar: leader, page 9. As the world marks the centenary of the October revolution, Russia is once again under the rule of a tsar. PoliticsShinzo Abe's gamble in calling an early general election in Japan paid off, as his ruling Liberal Democratic Party won 281 of the 465 contested seats in the lower house of parliament. Along with seats won by the ldp's coalition partner, Mr Abe has control of two-thirds of the house, meaning he can pass legislation without approval from the upper house. The prime minister will press to change Japan's pacifist constitution, a huge step that will allow it to take part more easily in peacekeeping operations, but will also rattle China and South Korea. Re-running scaredKenya reran its disputed presidential election, despite the opposition calling for a boycott. An appeal before the Supreme Court to postpone the ballot was not heard because five of the seven judges were absent amid claims of intimidation. Last month the court threw out the result of August's poll because the count had been mishandled. Not so flakyJeff Flake, a senator from Arizona and one of the more cerebral Republicans, denounced Donald Trump's presidency and the general state of his party from the Senate floor. Without naming Mr Trump, Mr Flake criticised the "coarseness of our leadership" and its "reckless, outrageous and undignified behaviour". He challenged his colleagues to speak up. Mr Flake has decided not to run for re-election next year. A disunited oppositionFour of the five opposition candidates who won elections for governor in Venezuela took their oaths before the constituent assembly, a sham parliament controlled by President Nicolas Maduro's United Socialist Party. They were criticised by the rest of the opposition. Yes, and noAndrej Babis, a billionaire and former finance minister, won a general election in the Czech Republic. Mr Babis's ano ("Yes") party took 30% of the vote. His victory was viewed as the latest triumph of a charismatic populist in central Europe, but with a splintered parliament, Mr Babis will have trouble forming a coalition. Solv'ng a stinking problemTo the relief of expatriates in the country, China lifted a ban on imports of mould-ripened cheese, which had been imposed because the bacteria used in making them had not been approved. Soft cheeses such as Brie, Gorgonzola and Stilton are much sought after by Westerners in China. Chinese officials allowed the cheeses back in after receiving assurances from European counterparts that they are safe. BusinessWall Street scored a big victory when the Senate scotched a proposed law that would have allowed customers of banks and credit-card companies to sue for malpractice through class-action lawsuits. The measure was put forward by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, an agency created under the Dodd-Frank reforms which has a rocky relationship with the banking industry. Its rule would have rewritten the requirement in retail-finance contracts that customers seekredressfor grievances through arbitration, rather than the courts. But the Treasury had criticised the proposal, for curtailing the "freedom of contract". A helping handThe Indian government announced a $32bn plan to recapitalise state-controlled banks. The banks, which hold two-thirds of India's banking assets, have been blamed for dragging down economic growth after a decade of unrestrained lending to industry, which has put a dent in their balance-sheets and constrained consumer lending. All eyes on the bankThe welcome news of better-than-expected growth figures in Britain was tempered by the increased likelihood of a rise in interest rates. gdp expanded by 0.4% in the third quarter compared with the previous three months. With inflation at 3%, the Bank of England has hinted that it will raise rates for the first time since 2007, possibly at its meeting on November 2nd. That would leave many households struggling; mortgage debt and consumer credit is running close to 140% of income. Withered on the vineThe world's production of wine will fall this year to its lowest level since 1961, according to the International Organisation of Vine and Wine, because of bad weather that has damaged the grape crop in Italy, France and Spain. Global output will drop by 8% compared with 2016, which leaves some 3bn fewer bottles of wine to sip. The recent wildfires in northern California will probably not have had too much of an effect on American production (most of the state's wine grape is grown in the Central Valley). A tsar is bornSeventeen years after Vladimir Putin first became president, his grip on Russia is stronger than ever. The West, which still sees Russia in post-Soviet terms, sometimes ranks him as his country's most powerful leader since Stalin. Russians are increasingly looking to an earlier period of history. Both liberal reformers and conservative traditionalists in Moscow are talking about Mr Putin as a 21st-century tsar. Firm ruleMr Putin is hardly the world's only autocrat. Personalised authoritarian rule has spread across the world over the past 15 years — often, as with Mr Putin, built on the fragile base of a manipulated, winner-takes-all democracy. It is a rebuke to the liberal triumphalism which followed the collapse of the Soviet Union. Leaders such as Recep Tayyip Erdogan of Turkey (see page 38), the late Hugo Chavez of Venezuela and even Narendra Modi, India's prime minister, have behaved as if they enjoy a special authority derived directly from the popular will. In China Xi Jinping this week formalised his absolute command of the Communist Party (see page 27). Mother Russia's offspringThe other lesson is about succession. The October revolution is just the most extreme recent case of power in Russia passing from ruler to ruler through a time of troubles. Mr Putin cannot arrange his succession using his bloodline or the Communist Party apparatus. Perhaps he will anoint a successor. But he would need someone weak enough for him to control and strong enough to see off rivals—an unlikely combination. Perhaps he will try to cling to power, as Deng Xiaoping did behind the scenes as head of the China Bridge Association, and Mr Xi may intend to overtly, having conspicuously avoided naming a successor after this week's party congress. Yet, even if Mr Putin became the eminence grise of the Russian Judo Federation, it would only delay the fatal moment. Without the mechanism of a real democracy to legitimise someone new, the next ruler is likely to emerge from a power struggle that could start to tear Russia apart. In a state with nuclear weapons, that is alarming. скачать журнал: The Economist - 28 октября 2017

|

Популярные книги и учебники

- Экономикс - Макконнелл К.Р., Брю С.Л. - Учебник

- Бухгалтерский учет - Кондраков Н.П. - Учебник

- Капитал - Карл Маркс

- Курс микроэкономики - Нуреев Р. М. - Учебник

- Макроэкономика - Агапова Т.А. - Учебник

- Экономика предприятия - Горфинкель В.Я. - Учебник

- Финансовый менеджмент: теория и практика - Ковалев В.В. - Учебник

- Комплексный экономический анализ хозяйственной деятельности - Алексеева А.И. - Учебник

- Теория анализа хозяйственной деятельности - Савицкая Г.В. - Учебник

- Деньги, кредит, банки - Лаврушин О.И. - Экспресс-курс

Новые книги и журналы

Популярные лекции

- Шпаргалки по бухгалтерскому учету

- Шпаргалки по экономике предприятия

- Аудиолекции по экономике

- Шпаргалки по финансовому менеджменту

- Шпаргалки по мировой экономике

- Шпаргалки по аудиту

- Микроэкономика - Лекции - Тигова Т. Н.

- Шпаргалки: Финансы. Деньги. Кредит

- Шпаргалки по финансам

- Шпаргалки по анализу финансовой отчетности

- Шпаргалки по финансам и кредиту

- Шпаргалки по ценообразованию

- 50 лекций по микроэкономике - Тарасевич Л.С. - Учебное пособие

Популярные рефераты

- Коллективизация в СССР: причины, методы проведения, итоги

- Макроэкономическая политика: основные модели

- Краткосрочная финансовая политика предприятия

- Марксизм как научная теория. Условия возникновения марксизма. К. Маркс о судьбах капитализма

- История развития кредитной системы в России

- Коммерческие банки и их функции

- Лизинг

- Малые предприятия

- Классификация счетов по экономическому содержанию

- Кризис отечественной экономики

- История развития банковской системы в России

- Маржинализм и теория предельной полезности

- Кризис финансовой системы стран Азии и его влияние на Россию

- Иностранные инвестиции

- Безработица в России

- Источники формирования оборотных средств в условиях рынка