Популярные статьи

- Государственно-частное партнерство: теория и практика

- Международный форум по Партнерству Северного измерения в сфере культуры

- Мировой финансовый кризис и его влияние на Россию

- Совершенствование оценки эффективности инвестиций

- Теория экономических механизмов

- Кластерный подход в стратегии инновационного развития зарубежных стран

- Качество и уровень жизни населения

- Фактор времени при оценке эффективности инвестиционных проектов

- Государственная собственность в российской экономике - Масштаб и распределение по секторам

- Вопросы оценки видов социального эффекта при реализации инвестиционных проектов

- Особенности нового этапа инновационного развития России

- Перспективы социально-экономического развития России

- Экономический кризис в России: экспертный взгляд

- Налоговые риски

Популярные курсовые

- Учет нематериальных активов

- Потребительское кредитование

- Бухгалтерский учет - Курсовые работы

- Финансы, бухгалтерия, аудит - курсовые и дипломные работы

- Денежная система и денежный рынок

- Долгосрочное планирование на предприятии

- Диагностика кризисного состояния предприятия

- Интеграционные процессы в современном мире

- Доходы организации: их виды и классификация

- Кредитная система: место и роль в ней ЦБ и коммерческих банков

- Международные рынки капиталов

- Многофакторный анализ производительности труда

- Непрерывный трудовой стаж

- Виды и формы собственности и трансформация отношений собственности в России

- Анализ финансово-хозяйственной деятельности

Навигация по сайту

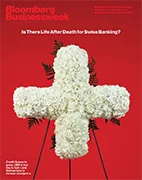

Bloomberg Businessweek Europe (April 3, 2023) |

| Скачать - Журналы | |||

|

Год выпуска: April 3, 2023 Автор: Bloomberg Businessweek Europe Жанр: Бизнес Издательство: «Bloomberg Businessweek USA» Формат: PDF (журнал на английском языке) Качество: OCR Количество страниц: 68 Can Anyone Fix This?UBS takes over Credit Suisse to save it, and the future of Swiss banking is at stakeMarcel Ospel, the Swiss banker dubbed “Herr der UBS,” or “Master of UBS,” by his biographer, had a story about what happens when the mighty fall. He built UBS Group AG into a global behemoth, and became one of the leading financial figures of his time, only to see the bank come close to collapse during the 2008 financial crisis. Scorned as a national failure, Ospel later bumped into a lawyer he knew. He got the cold shoulder. “When I was head of UBS,” he sadly recalled to the biographer, “this guy would do anything I wanted.” Ospel didn’t live to see today’s great humbling in Zurich (he died in 2020, at age 70). But his sentiment then-once we were kings, all things must pass-seems even more apt now. Fifteen years after UBS had to be bailed out, rival Credit Suisse Group AG has collapsed into its arms. The twin pillars of Swiss banking as the world has known them have become one monolith towering over the local competition. Just about everything that once made Switzerland a byword for world-class financestability and discretion combined with global ambition-has been tested and found wanting. “The damage to Switzerland’s reputation is going to be terrible,” says Arturo Bris, a professor of finance at IMD business school in Lausanne. This UBS-Credit Suisse deal, hastily brokered by Bern, will alter the world’s financial landscape. Even before this shock, Singapore-the humid Switzerland of Asia-was closing in on the private-wealth managers of Zurich and Geneva. This will only speed the rise of Switzerland’s international rivals. In this context, personnel is political. Reverting to a tradition of having a Swiss executive hold one of the top two jobs at the bank, UBS on March 29 announced that Dutchman Ralph Hamers would be replaced as chief executive officer by Lugano-born Sergio Ermotti, who ran the bank from 2011 to 2020. Chairman Colm Kelleher, who is Irish, said in a press conference that Ermotti’s citizenship is a “nice thing” but didn’t determine the choice. Regulators encouraged UBS to bring Ermotti back, people familiar with the talks told Bloomberg News. How did Switzerland’s banks get here? Slowly, then all at once. For much of its history, Credit Suisse stood at the pinnacle of world finance, bankrolling 19th century Swiss railroads and 20th century Silicon Valley and tending the fortunes of the rich from the French Riviera to Russia. And yet, Credit Suisse had been a slow-motion train wreck for decades. Its first stumbles can be traced as far back as the 1980s, when it began tilting at the giants of Wall Street. Credit Suisse swallowed First Boston Corp., a Wall Street bank with an appetite for risk. Then, at the height of the ’90s dot-com bubble, it acquired midtier Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette, which turned out to be a costly fumble as top DLJ bankers headed for the door. And then: scandal after scandal after scandal after scandal. There was the massive “Suisse Secrets” leak to the press that exposed the hidden wealth of clients involved in drug trafficking, kleptocracy and money laundering. And the top banker who defrauded a clutch of Georgian and Russian clients while the bosses ignored red flags, a court concluded. And the corporate espionage saga that led to the ouster in 2020 of then-CEO Tidjane Thiam, though he was absolved of personal responsibility in an internal probe. And those two infamous blowups in 2021: Stock trader Bill Hwang managed to lose billions of dollars using Credit Suisse loans, and the collapse of fintech entrepreneur Lex Greensill’s business forced the bank to freeze $10 billion of supply chain finance funds it had marketed as safe. In October the latest CEO of Credit Suisse, Ulrich Koerner - the third in as many years-unveiled a plan to fix the mess once and for all. He never got the chance. With financial markets on edge after the March 10 collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, all it took was one spark to set Credit Suisse ablaze. When the chairman of Saudi National Bank, Credit Suisse’s biggest shareholder, told Bloomberg News that his bank would “absolutely not” increase its stake, primarily for regulatory reasons, investors panicked, and the desperate race to broker a rescue deal was on. (Twelve days later, the Saudi bank chairman resigned, citing personal reasons.) Initially, UBS looked like the only winner, particularly given generous government guarantees that came with the deal. Swiss authorities tore up the playbook they’d written following the 2008 financial crisis. Shareholders were left with scraps. Holders of $17 billion of Credit Suisse’s so-called СoСo bonds-sometimes described as high-yield investments with a hand grenade attached-got wiped out. Swiss taxpayers have been left with a bank far bigger than this country of 8.7 million people should have to worry about. Maybe it was the least bad plan. Finance Minister Karin Keller-Sutter told one Swiss newspaper that the bank wouldn’t have survived one more working day and that “we should have expected a global financial crisis,” as “the crash of CS would have sent other banks into the abyss.” Andrea Schenker-Wicki, an economist and president of the University of Basel, says the Swiss government prevented a global panic-for now. The question is what happens later should UBS ever run into trouble. “To me, it means that a problem of the present has been fixed, but a future problem has been created,” Schenker-Wicki says. Others have similar qualms. By letting UBS buy Credit Suisse on its own favorable terms, the staid, orderly Swiss may have set the stage for future calamity. “To paraphrase Warren Buffett, the new, expanded UBS might well become a financial weapon of mass destruction, capable in a collapse of taking down the entire Swiss economy with it,” says Jared Bibler, a former regulator at the Swiss Stock Exchange. The irony is that Switzerland spent 15 years workshopping its financial-crisis strategy-and then ignored it. “All other options were more risky for the state,” Keller-Sutter said in the newspaper interview. To get the deal done, Swiss authorities invoked an emergency clause in the constitution that enabled them to waive shareholder rights and suspend an antitrust probe-a rare if not unprecedented step in the nation’s financial markets. Expect lawsuits. Markets can have short memories. But private-wealth clients and investors are unlikely to forget this one. For many, the UBS-Credit Suisse deal has badly tarnished Switzerland’s image abroad. “Right now, Singaporeans are opening the Champagne,” says Bris, the IMD professor. “This is going to be the turning point.” As for Swiss banking, yes, other, smaller players will endure and even prosper in the vast shadow of UBS-like Banque Pictet & Cie. and Banque Lombard Odier & Cie. Although private banks manage hundreds of billions of dollars in assets, these are hardly the Goldmans or JPMorgan Chases of global finance with both wealth management and investment banking arms. Meanwhile, Wall Street heavyweights and banks from Europe will almost certainly cast an eye toward Switzerland as a place to open up shop now that there’s one fewer competitor to deal with. And Geneva, a city often looked down upon among Zurich bankers as not properly Swiss and as a haven for dirty money, will benefit, too. Wealthy investors who once split their fortunes between UBS and Credit Suisse will be inclined to shop around. “There is going to be a diversification effect,” Lombard Odier senior partner Hubert Keller told Bloomberg News. For all the problems UBS will be inheriting-from ongoing legal cases to one whopper of an integration headache-it gives the bank huge opportunities. It now reenters the top 20 global banks, as measured by total assets, and will become the second-largest global wealth manager behind Morgan Stanley and the third-biggest asset manager in Europe. But back home, this is going to take some adjusting. Visit any small town in Switzerland, and there’s almost always a branch of both Credit Suisse and UBS. A typical person might have a bank account with UBS, a mortgage with Credit Suisse and a pension fund managed by UBS. That choice narrows once this deal is done, leaving customers potentially facing higher costs or being pushed to smaller rivals that are less well-equipped to offer sophisticated international banking services. Opinion polls in Switzerland show more than half of people oppose the merger and only 1 in 20 fully endorse it. Already, there’s political pressure to spin off Credit Suisse’s domestic banking unit from the new giant. Switzerland could become a more expensive place to negotiate a mortgage or raise capital because UBS no longer has to hustle against its main rival. That will undermine the ability of export-oriented companies to compete abroad. Clariant AG, a Swiss specialty chemicals maker, stuck its head above the parapet to express its displeasure with the deal and specifically what it believes will be UBS’s newfound pricing power. “It is certainly not good that there is now only one big bank,” a Clariant spokesperson told Bloomberg News. Credit Suisse had signaled it planned to cut 9,000 jobs worldwide as part of the restructuring plan that never was. Add to that the redundancies expected from the merger-the two banks together have about 37,000 staff in Switzerland already-and the number is expected to tick much higher. The sense of gloom on Paradeplatz, the grand square in Zurich where Credit Suisse is headquartered, is almost palpable. “It’s very bad at the moment-we have lost trust in this institution,” says Tomas Prenosil, CEO of luxury confectioner Confiserie Spruengli, inside the company’s flagship cafe on the square, a spot it’s occupied since 1859- Cutting jobs, of course, has an impact on surrounding businesses. “Many bank employees are longtime and loyal customers,” he says. Above all, Swiss banking will have to become more boring, a necessary antidote to avoid repeating the excessive risk-taking and ensuing scandals that led to Credit Suisse’s demise. The deal and the emergency ordinances needed to shoehorn it through will be the focus of an extraordinary assembly of the Swiss parliament in April. The politicians may think they’re in control, but right now the bankers at UBS seem more powerful, says Bibler, the former regulator: “We all work for UBS now.” — Hugo Miller and Jan-Henrik Foerster, with Paula Doenecke, Marion Halftermeyer and Myriam Balezou Hasbro’s Hollywood Fantasy

The Preacher and the Ponzi

Hagerty’s Wild Ride

IN BRIEF

OPINION

AGENDA

REMARKS

BUSINESS

TECHNOLOGY

FINANCE

ECONOMICS

SOLUTIONS / SMALL BUSINESS

PURSUITS

LAST THING

скачать журнал: Bloomberg Businessweek Europe (April 3, 2023)

|

Новые книги и журналы

Популярные книги и учебники

- Экономикс - Макконнелл К.Р., Брю С.Л. - Учебник

- Бухгалтерский учет - Кондраков Н.П. - Учебник

- Капитал - Карл Маркс

- Курс микроэкономики - Нуреев Р. М. - Учебник

- Макроэкономика - Агапова Т.А. - Учебник

- Экономика предприятия - Горфинкель В.Я. - Учебник

- Финансовый менеджмент: теория и практика - Ковалев В.В. - Учебник

- Комплексный экономический анализ хозяйственной деятельности - Алексеева А.И. - Учебник

- Теория анализа хозяйственной деятельности - Савицкая Г.В. - Учебник

- Деньги, кредит, банки - Лаврушин О.И. - Экспресс-курс

Популярные рефераты

- Коллективизация в СССР: причины, методы проведения, итоги

- Макроэкономическая политика: основные модели

- Краткосрочная финансовая политика предприятия

- История развития кредитной системы в России

- Марксизм как научная теория. Условия возникновения марксизма. К. Маркс о судьбах капитализма

- Коммерческие банки и их функции

- Лизинг

- Малые предприятия

- Классификация счетов по экономическому содержанию

- Кризис отечественной экономики

- История развития банковской системы в России

- Маржинализм и теория предельной полезности

- Иностранные инвестиции

- Безработица в России

- Кризис финансовой системы стран Азии и его влияние на Россию

- Источники формирования оборотных средств в условиях рынка

Популярные лекции

- Шпаргалки по бухгалтерскому учету

- Шпаргалки по экономике предприятия

- Аудиолекции по экономике

- Шпаргалки по финансовому менеджменту

- Шпаргалки по мировой экономике

- Шпаргалки по аудиту

- Микроэкономика - Лекции - Тигова Т. Н.

- Шпаргалки: Финансы. Деньги. Кредит

- Шпаргалки по финансам

- Шпаргалки по анализу финансовой отчетности

- Шпаргалки по финансам и кредиту

- Шпаргалки по ценообразованию