Популярные статьи

- Государственно-частное партнерство: теория и практика

- Международный форум по Партнерству Северного измерения в сфере культуры

- Мировой финансовый кризис и его влияние на Россию

- Совершенствование оценки эффективности инвестиций

- Теория экономических механизмов

- Кластерный подход в стратегии инновационного развития зарубежных стран

- Качество и уровень жизни населения

- Фактор времени при оценке эффективности инвестиционных проектов

- Государственная собственность в российской экономике - Масштаб и распределение по секторам

- Вопросы оценки видов социального эффекта при реализации инвестиционных проектов

- Особенности нового этапа инновационного развития России

- Перспективы социально-экономического развития России

- Экономический кризис в России: экспертный взгляд

- Налоговые риски

Популярные курсовые

- Учет нематериальных активов

- Потребительское кредитование

- Бухгалтерский учет - Курсовые работы

- Финансы, бухгалтерия, аудит - курсовые и дипломные работы

- Денежная система и денежный рынок

- Долгосрочное планирование на предприятии

- Диагностика кризисного состояния предприятия

- Интеграционные процессы в современном мире

- Доходы организации: их виды и классификация

- Кредитная система: место и роль в ней ЦБ и коммерческих банков

- Международные рынки капиталов

- Многофакторный анализ производительности труда

- Непрерывный трудовой стаж

- Виды и формы собственности и трансформация отношений собственности в России

- Анализ финансово-хозяйственной деятельности

Навигация по сайту

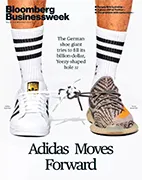

Bloomberg Businessweek (May 29, 2023) |

| Скачать - Журналы | |||

|

Год выпуска: May 29, 2023 Автор: Bloomberg Businessweek Жанр: Бизнес Издательство: «Bloomberg Businessweek» Формат: PDF (журнал на английском языке) Качество: OCR Количество страниц: 68 Adidas Moves ForwardRemember when Yeezy made Adidas the hottest shoe company in the world?How the biggest collab since Nike met Jordan went so wrongMILLIONS OF PAIRS OF UNSOLD Yeezys are sitting in purgatory, stacked in warehouses from the US to China. Sneakers-some looking like cozy turtleneck sweaters for your feet, others like they’ve grown teeth on their soles or solidified into pillowy clouds-that once would’ve sold out in limited-edition drops, often flipped for much more on StockX and Goat, now await their fate seven months after one of the biggest corporate meltdowns in history. Their owner, Adidas AG, couldn’t decide what to do with all the tarnished merchandise created by the man who was, until recently, its most prominent business partner: Kanye West, who now goes by Ye. The total value of these sneakers: about $1.3 billion. At Adidas headquarters in the medieval town of Herzogenaurach, Germany, senior executives have spent months mulling their Yeezy inventory dilemma. They’ve considered unstitching the Yeezy logo off each sneaker, one by one, but that’s too laborious. They contemplated donating the goods to victims in disaster-struck countries such as Turkey and Syria, but that could trigger illicit trafficking. Burning them in the world’s largest hypebeast bonfire would be an environmental calamity, and chopping them into plastic bits to be reborn as turf is overly complicated and hardly satisfying. Management finally decided it would begin selling the sneakers while giving a portion of the proceeds to charities. The first of the stranded footwear will be available for purchase at the end of May. Over the last few years, one of Germany’s largest companies became dangerously reliant on a single person to meet its towering financial goals. Then, in October, Ye capped off a series of unhinged outbursts with a torrent of antisemitic rants, leaving Adidas little choice but to end its multibillion-dollar arrangement with Yeezy and eliminating nearly half the company’s earnings in an instant. By the time the partnership dissolved, the shoes accounted for 8% of Adidas’s total revenue and 40% of its profit, according to estimates from Morgan Stanley. Even worse, the collapse exposed deep-rooted problems at Adidas that Yeezy’s success had long camouflaged. Ye should never have generated such a big chunk of earnings, and he didn’t-until the bottom fell out elsewhere in the company. Product cycles went out of whack as Adidas flooded the market with anything that showed promise, often resorting to its vintage standbys. Collaborations with Beyonce and Prada fell short. Leadership grossly miscalculated its pandemic strategy, then lost footing in two of its most vital overseas markets. Now Adidas is faced with life after Yeezy. Last fall its board of supervisors decided to cough up $17 million to push out Chief Executive Officer Kasper Rorsted more than three years before his contract was set to expire. Rather than gamble on an up-and-coming visionary type for a new CEO, the board went with a far more sensible bet: Bjorn Gulden, the successful head of crosstown rival Puma. In February, after only a few weeks acquainting himself with Adidas’s books, Gulden issued one of the bleakest financial forecasts in the company’s history. Adidas expects to lose more than $700 million this year, its first operating loss since the early 1990s. Before the company can even think about profitable growth, it needs to resort to huge discounts to unload more than $6 billion of unsold sneakers and apparel, largely the result of supply chain snarls and overestimated demand, an industrywide problem that many of its competitors have already resolved. “Adidas needs a complete overhaul after the Yeezy disaster,” says Janne Werning, head of ESG capital markets and stewardship at German shareholder Union Investment. “After these lost years, Gulden has a lot of work ahead of him.” But even Gulden had no easy answers to questions about Yeezy. He praised the partnership from the point of view of product design, distribution and marketing. “It was a fantastic combination,” he said. “Unfortunately, it’s now lost, and it’s something that we need then to replace with many, many, many pieces.” ADIDAS AND NIKE MIGHT BE ETERNAL rivals, but the battle between Adidas and Puma is personal. Adolf “Adi” Dassler and his brother, Rudolf, both members of the Nazi Party, ran a shoemaking business together until they had a bitter falling out during World War II, when Rudolf fought in Poland while Adi stayed home to run their factory. Rudolf started his own company, Puma, in 1948, and Adi started Adidas a year later. The ensuing rupture split the family in two, along with the surrounding town of Herzogenaurach-Herzo, as locals call it. Residents got sucked into the sibling rivalry, with thousands working for one brother or the other. For decades after the war, the Dasslers dominated sports from basketball and track to the Olympics and the World Cup, but their hostilities over market share and bragging rights were so intense that by the 1970s they failed to appreciate the rise of an upstart in Oregon. Adi Dassler never saw his company dethroned. He died in 1978-four years after his brother-of heart failure, just before Adidas made a decision that would forever haunt it. In 1984, Adidas and Nike looked into signing a college basketball star named Michael Jordan to a shoe deal before he’d even stepped onto an NBA court. Sneaker sponsorships were nothing new: Adi Dassler famously persuaded Jesse Owens to wear his spikes at the 1936 Berlin Olympics. The Dasslers had even pioneered the sports-inspired lifestyle category-Puma churning out hits like the Walt “Clyde” Frazier basketball shoe and Adidas later becoming the first brand to dive into street culture when it paid hip-hop group Run-DMC to wear its tracksuits and hawk the brand in the song My Adidas in the mid-1980s. Two marketing hotshots at Nike, Rob “Rolling Thunder” Strasser and Peter Moore, offered Jordan an unprecedented endorsement deal flush with royalties, a high salary and a personal shoe brand called Air Jordan. Even though Jordan was a die-hard Adidas fan, Adidas didn’t want to pay that kind of money. The year Air Jordans made their debut, Nike made $126 million in revenue from the line, according to Jordan’s agent. By the end of the ’80s, Adidas had fallen to third place in the industry, trailing Nike and Reebok. The Nike-Jordan partnership scrambled the dynamics of the sneaker industry. Before Adidas passed on Jordan, about 75% of pro basketball players wore the stripes on the court. Nike quickly took near-total control of basketball; because of the sport’s cultural significance in the US, the world’s single biggest sports market, this shift was seismic. For decades, a common gripe from Adidas employees in the US was that their leaders in Germany failed to appreciate American culture. It wasn’t until the 1990s, after the Dasslers lost control of the company and Strasser and Moore defected to Adidas, that it was ready to fight back. When Moore flew to Adidas HQ, he marveled at its archive of products, including the three-striped white boots worn by boxing legend Muhammad Ali. “This guy Adi was the father of 90% of the industry,” Moore recalled, according to Portland Monthly. His other thought: How had Adidas managed to “f— it up so bad?” Strasser and Moore introduced a new line of no-frills athletic sneakers and apparel, channeling the brand’s performance origins. But Strasser died suddenly of heart failure at age 46. Moore briefly took over as head of Adidas’s US operations, while the wealthy French businessman Robert Louis-Dreyfus became CEO and took the company public. Following him was German executive Herbert Hainer, who bought Reebok for about $3.8 billion in a gambit to compete with Nike in the US. Among the many employees Moore groomed at Adidas was a lanky swimmer named Eric Liedtke. After working at the Adidas office in Portland, Oregon, he was shipped off to Germany where he oversaw the development of Boost, the spongey cushioning technology that Adidas developed with German chemicals maker BASF. At last, Adidas had an answer to Nike’s decades-old midsole platform Air and it revolutionized Adidas’s line of running shoes. In 2014, Liedtke became the company’s first-ever American head of global brands. “Herbert Hainer basically came to me and said, ‘Hey Eric, two things: You’ve got to reset the brand. Do what it takes, and don’t ask me for permission, ask for advice,’” Liedtke recalls. He set out to finally create Adidas’s Jordan. KANYE WEST HAD ALWAYS LOVED Nike, not Adidas. In late 2006, less than a year after Mark Parker was named CEO of Nike, he invited West to perform at Manhattan’s Gotham Hall in front of a celebrity crowd that included director Spike Lee and New York Knicks legend Patrick Ewing. They were there to celebrate the 25th anniversary of Nike’s Air Force is, with 1,000 pairs on display throughout the venue. West would later be photographed on a private jet with Parker, sketching shoe ideas for Nike. Over the next few years, as the rapper released several albums, he and Nike developed the Air Yeezy together. The shoe came out in 2009, followed by a second iteration three years later. They’re still some of the most coveted sneakers of all time-today a pair of Nike Air Yeezy 2 Red October high-tops, which look like 3D-printed sneakers made of plastic mesh strawberries, can sell for $15,000 or more. The relationship soured when West demanded royalties from every pair sold. “Nike told me, ‘We can’t give you royalties, because you’re not a professional athlete,’ ” West said after they cut ties. “I told them, ‘I go to the Garden and play one-on-no-one. I’m a performance athlete.’” West met quietly with Adidas executives in New York during a rehearsal session for Jimmy Fallon’s talk show... Yeezy Come, Yeezy Go

Sergey in the Sky With Airships

Herding Out the Shepherds

IN BRIEF

OPINION

AGENDA

REMARKS

BUSINESS

TECHNOLOGY

FINANCE

ECONOMICS

SOLUTIONS/CYBERSECURITY

PURSUITS

LAST THING

скачать журнал: Bloomberg Businessweek (May 29, 2023)

|

Новые книги и журналы

Популярные книги и учебники

- Экономикс - Макконнелл К.Р., Брю С.Л. - Учебник

- Бухгалтерский учет - Кондраков Н.П. - Учебник

- Капитал - Карл Маркс

- Курс микроэкономики - Нуреев Р. М. - Учебник

- Макроэкономика - Агапова Т.А. - Учебник

- Экономика предприятия - Горфинкель В.Я. - Учебник

- Финансовый менеджмент: теория и практика - Ковалев В.В. - Учебник

- Комплексный экономический анализ хозяйственной деятельности - Алексеева А.И. - Учебник

- Теория анализа хозяйственной деятельности - Савицкая Г.В. - Учебник

- Деньги, кредит, банки - Лаврушин О.И. - Экспресс-курс

Популярные рефераты

- Коллективизация в СССР: причины, методы проведения, итоги

- Макроэкономическая политика: основные модели

- Краткосрочная финансовая политика предприятия

- История развития кредитной системы в России

- Марксизм как научная теория. Условия возникновения марксизма. К. Маркс о судьбах капитализма

- Коммерческие банки и их функции

- Лизинг

- Малые предприятия

- Классификация счетов по экономическому содержанию

- Кризис отечественной экономики

- История развития банковской системы в России

- Маржинализм и теория предельной полезности

- Иностранные инвестиции

- Безработица в России

- Кризис финансовой системы стран Азии и его влияние на Россию

- Источники формирования оборотных средств в условиях рынка

Популярные лекции

- Шпаргалки по бухгалтерскому учету

- Шпаргалки по экономике предприятия

- Аудиолекции по экономике

- Шпаргалки по финансовому менеджменту

- Шпаргалки по мировой экономике

- Шпаргалки по аудиту

- Микроэкономика - Лекции - Тигова Т. Н.

- Шпаргалки: Финансы. Деньги. Кредит

- Шпаргалки по финансам

- Шпаргалки по анализу финансовой отчетности

- Шпаргалки по финансам и кредиту

- Шпаргалки по ценообразованию