Популярные статьи

- Государственно-частное партнерство: теория и практика

- Международный форум по Партнерству Северного измерения в сфере культуры

- Мировой финансовый кризис и его влияние на Россию

- Совершенствование оценки эффективности инвестиций

- Теория экономических механизмов

- Кластерный подход в стратегии инновационного развития зарубежных стран

- Качество и уровень жизни населения

- Фактор времени при оценке эффективности инвестиционных проектов

- Государственная собственность в российской экономике - Масштаб и распределение по секторам

- Вопросы оценки видов социального эффекта при реализации инвестиционных проектов

- Особенности нового этапа инновационного развития России

- Перспективы социально-экономического развития России

- Экономический кризис в России: экспертный взгляд

- Налоговые риски

Популярные курсовые

- Учет нематериальных активов

- Потребительское кредитование

- Бухгалтерский учет - Курсовые работы

- Финансы, бухгалтерия, аудит - курсовые и дипломные работы

- Денежная система и денежный рынок

- Долгосрочное планирование на предприятии

- Диагностика кризисного состояния предприятия

- Интеграционные процессы в современном мире

- Доходы организации: их виды и классификация

- Кредитная система: место и роль в ней ЦБ и коммерческих банков

- Международные рынки капиталов

- Многофакторный анализ производительности труда

- Непрерывный трудовой стаж

- Виды и формы собственности и трансформация отношений собственности в России

- Анализ финансово-хозяйственной деятельности

Навигация по сайту

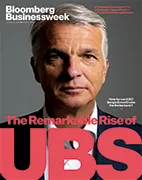

Bloomberg Businessweek (October 23, 2023) |

| Скачать - Журналы | |||

|

Год выпуска: October 23, 2023 Автор: Bloomberg Businessweek Жанр: Бизнес Издательство: «Bloomberg Businessweek» Формат: PDF (журнал на английском языке) Качество: OCR Количество страниц: 68 The Swiss SolutionSergio Ermotti is back at the helm of UBS—and looking to capitalize on the deal of a lifetimeOn a Saturday in March this year, FC Collina d’Oro was grinding its way to a 1-1 draw against Zug 94, rivals in a Swiss amateur league. The soccer ground in the south of the country is a modest one—no grandstands, just bleachers in the open air—but it’s perched on a hillside above Lake Lugano and surrounded by Alpine peaks. The club’s president, Sergio Ermotti, was trying to keep his mind on the players, but his phone wouldn’t stop buzzing—and the numbers looked vaguely familiar. Credit Suisse, the 167-year-old pillar of Swiss banking, had ended that week close to bankruptcy; officials in Bern, the country’s capital, were already attempting to engineer an emergency rescue. Only when the whistle blew for halftime, with the two teams deadlocked, did he return the calls. As the former chief executive officer of UBS Group AG, the biggest bank in Switzerland and a wealth manager of global standing, Ermotti was more than an average spectator—and soon enough he’d be pulled into the biggest contest of his career. In the rescue plan hammered out that weekend, UBS would ultimately buy its former rival for just $3.8 billion. It was also quickly evident that the CEO of UBS at the time, Ralph Hamers, a Dutch national with little experience in the complexities of investment banking or wealth management, was not the man for the job. Two weeks later, Ermotti was in a temporary office at UBS’s monumental headquarters in Zurich, getting ready for his second term running the bank after giving up his role as chairman of reinsurer Swiss Re. It was “surreal” to be back less than three years after stepping down, he told Bloomberg Businessweek in an exclusive interview in Zurich on Oct. 11. But “after 48 hours, it was almost like I’d never left.” In the months since, investors have enthusiastically backed Ermotti’s plan to chop up Credit Suisse and use the choicest bits to buttress his own bank. UBS’s shares have risen by almost a third since March. It’s preparing to cut tens of thousands of jobs over the coming years, with a confirmed 3,000 in Switzerland alone. Yet the Swiss establishment has more or less given UBS a free hand. The disappearance of one of the country’s two global banks generated some political grumbling, and finance minister Karin Keller-Sutter’s Free Democrats party has taken a dent in the polls before an Oct. 22 general election. For this vote, however, the Swiss seem more urgently concerned with rising health-care costs and immigration. In his first decade at UBS, Ermotti was a stabilizing force. The bank had required a state bailout during the global financial crisis, and a roguetrading scandal in 2011 further rocked its reputation. Although Ermotti overhauled the bank’s playbook, swapping the volatility of investment banking for the steadiness of wealth management, the overall growth strategy at the time of his 2020 departure remained vague. Hamers, in charge for less than three years, failed to set a clearer path. Ermotti is now making amends and laying the groundwork for UBS’s growth strategy far beyond the absorption of Credit Suisse. “I see my mandate as not only about integrating the bank,” he says. “The true, real legacy is also to prepare the bank for the next chapter.” If he plays everything right, Ermotti can use Credit Suisse to bulletproof UBS as the undisputed global wealth champion far beyond his own tenure. The core of that transition will be to harness Credit Suisse’s more muscular, US-focused investment bank to serve America’s ultrawealthy, challenging the Wall Street giants on their own turf. UBS will report third-quarter earnings on Nov. 7. A key point to watch will be the extent to which UBS’s profits can absorb the bleeding at Credit Suisse. The latter expects a loss of some $2 billion for the period, as some business areas are wound down. The integration of Credit Suisse comes with a raft of potential difficulties, from closing out positions to managing the legal liabilities inherited from UBS’s rival. The combined bank is entangled in a long list of lawsuits, as well as a US Department of Justice probe into suspected compliance failures that allowed Russian clients to evade sanctions. UBS’s ascent to becoming the only properly global wealth manager began in the 1990s, following the merger of its antecedent institutions, Swiss Bank Corp. and Union Bank of Switzerland. Like its peers, UBS went after the fortunes to be made in the newly liberalized world economy, as globalization went into hyperdrive following the fall of the Soviet Union. It still traded on its founding Swiss values of “confidence, security and discretion,” which helped secure business in rapidly developing economies, notably in Asia. In Chinese, the characters used for “UBS” simply mean “Swiss Bank.” A sign of UBS’s standing is its claim that it banks more than half the world’s billionaires. That’s focused efforts on building piles of money into mountains of cash for the so-called ultrahigh-net-worth bracket, a broad category that means having at least $50 million or so to invest. And yet, UBS remains a relative minnow on Wall Street, being just one of several European lenders that have tried, and mostly failed, to make it big trading and doing deals there. Deutsche Bank AG closed its equities business in 2019, while HSBC Holdings Plc said in 2021 it would divert capital from its investment bank in New York to fund its pivot to Asia. (Ermotti’s own scaling back around 2012 involved exiting most debt-trading activities.) Now, UBS, one of the best-valued major European institutions, wants to take a second run at the US, but this time in the more staid business of managing wealth—and in the largest market for such services in the world. The challenge is still stiff. Rivals such as Morgan Stanley have much bigger client networks and bigger investment banks to craft whizzy financial products for them. UBS has also already suffered setbacks in trying to scale up its wealth management offering in the US. The latest was the $1.4 billion deal under Hamers to buy robo-adviser Wealthfront Corp. in 2022, which had been abandoned by the time the Credit Suisse acquisition came to pass. UBS’s valuation has accordingly trailed that of Wall Street’s titans, and Chairman Colm Kelleher has made little secret that he thinks it should be higher—as high, perhaps, as that of Morgan Stanley, where the Irishman spent most of his career. For Ermotti, boosting UBS’s second-rate presence in the US would fix a glaring deficit at the heart of the bank’s long-term strategy, a deficit he didn’t manage to address last time on the job. “No one else in the industry has had this kind of chance,” says Christoph Kuenzle, a lecturer on wealth management at Zurich University of Applied Sciences. “In UBS’s 150 years of history, this was the one big opportunity, almost for free. I think they would really have to mess up for it not to work out for them.” Ermotti was born in 1960 in Lugano, the largest city in the canton of Ticino—an Italian-speaking area that serves as something of a Riviera for landlocked Switzerland. There’s a Mediterranean climate and easy access to the lakes and mountains that form the border with Italy. In terms of its presence in Switzerland’s business and political life, though, Ticino tends to be overshadowed by the German- and French-speaking regions. “Ermotti is attached to Ticino,” says Christian DePrati, a childhood friend who worked at Credit Suisse First Boston and Merrill Lynch and still stays in touch with him. “It is one of his strengths to be really grounded and not losing contact with reality. He knows what his roots are.” He’s also fiercely competitive, which manifests in his passion for soccer. As a young man, he played for his local team and even dreamed of becoming a professional. Once, in a soccer match organized for a bachelor weekend, DePrati says, Ermotti scored a goal so spectacular that he was given the nickname Pinturicchio, after Italian national star Alessandro Del Piero. But Ermotti eventually switched his ambitions to finance. He’d taken an apprenticeship at Corner Bank in 1975, where he stayed about a decade in various roles. Merrill Lynch hired him in 1987, where he worked until the early 2000s. He ran investment banking and served as deputy CEO at Italian lender UniCredit SpA, joining UBS in a regional role in 2011, before being appointed CEO in the same year. At UBS, Ermotti’s strategic pivot away from investment banking and toward wealth management capitalized on one of the financial industry’s recent megatrends. In a world of low interest rates, the humdrum business of checking accounts and mortgages presented a challenging environment for financial institutions. Ditto investment banking, where the turbulence of arranging share sales and advising on company mergers led to a proliferation of losses. Yet the astonishing rise of global financial wealth on the back of an historic surge in asset prices these past three decades has provided a banking bonanza for a lucky few in New York, Zurich and Singapore... Exporting American Gun Culture

Chip Wilson’s $100 Million Cure

Out of the Park

IN BRIEF

OPINION

AGENDA

REMARKS

BUSINESS

TECHNOLOGY

FINANCE

ECONOMICS

PURSUITS / SKI SPECIAL

LAST THING

скачать журнал: Bloomberg Businessweek (October 23, 2023)

|

Новые книги и журналы

Популярные книги и учебники

- Экономикс - Макконнелл К.Р., Брю С.Л. - Учебник

- Бухгалтерский учет - Кондраков Н.П. - Учебник

- Капитал - Карл Маркс

- Курс микроэкономики - Нуреев Р. М. - Учебник

- Макроэкономика - Агапова Т.А. - Учебник

- Экономика предприятия - Горфинкель В.Я. - Учебник

- Финансовый менеджмент: теория и практика - Ковалев В.В. - Учебник

- Комплексный экономический анализ хозяйственной деятельности - Алексеева А.И. - Учебник

- Теория анализа хозяйственной деятельности - Савицкая Г.В. - Учебник

- Деньги, кредит, банки - Лаврушин О.И. - Экспресс-курс

Популярные рефераты

- Коллективизация в СССР: причины, методы проведения, итоги

- Макроэкономическая политика: основные модели

- Краткосрочная финансовая политика предприятия

- История развития кредитной системы в России

- Марксизм как научная теория. Условия возникновения марксизма. К. Маркс о судьбах капитализма

- Коммерческие банки и их функции

- Лизинг

- Малые предприятия

- Классификация счетов по экономическому содержанию

- Кризис отечественной экономики

- История развития банковской системы в России

- Маржинализм и теория предельной полезности

- Иностранные инвестиции

- Безработица в России

- Кризис финансовой системы стран Азии и его влияние на Россию

- Источники формирования оборотных средств в условиях рынка

Популярные лекции

- Шпаргалки по бухгалтерскому учету

- Шпаргалки по экономике предприятия

- Аудиолекции по экономике

- Шпаргалки по финансовому менеджменту

- Шпаргалки по мировой экономике

- Шпаргалки по аудиту

- Микроэкономика - Лекции - Тигова Т. Н.

- Шпаргалки: Финансы. Деньги. Кредит

- Шпаргалки по финансам

- Шпаргалки по анализу финансовой отчетности

- Шпаргалки по финансам и кредиту

- Шпаргалки по ценообразованию